In this episode of The Show About Science, Nate heads to the banks of the Chicago River to meet up with Melissa Pierce, PhD, the Technical Program Director at Current, a nonprofit water innovation hub. Together, they explore the complex world of urban water chemistry, focusing on the river’s historical pollution problems and the measures taken to improve the water quality, in particular, an in-depth look at Current’s H2Now program. In the second part of the episode, Nate travels to Washington, DC, to chat with Steve MacAvoy, PhD, a professor at American University. Steve’s research has centered around studying the impact of urban infrastructure on river water chemistry and how the rising concentrations of specific chemicals are impacting our waterways.

Episode Resources:

H2NOW website: https://www.h2nowchicago.org/

Current’s website: https://www.currentwater.org/

River Lab: https://www.currentwater.org/river-lab

Listen to The Show About Science on Storybutton, the device that makes it easy for kids to listen to podcasts without using a screened device. Get yours at Storybutton.com.

Connect with The Show About Science:

Instagram: @showaboutscience

Facebook: @theshowaboutscience

YouTube:The Show About Science

Twitter: @natepodcasts

LinkedIn: The Show About Science

Threads: showaboutscience

Transcript

Nate: Nate here, back with another episode of The Show About Science. And today, we’re beginning in the heart of the Windy City.

Melissa Pierce: So we are on the Chicago River. We’re in what’s considered the main stem on the Riverwalk right in downtown Chicago.

Nate: As you can probably tell by the noises.

Melissa Pierce: Yes.

Nate: This is Dr. Melissa Pierce.

Melissa Pierce: I am the Technical Program Director at Current. We are a nonprofit water innovation hub based in Chicago.

Nate: Melissa and I are here to delve into the mysterious world of urban water chemistry and to discuss how to study a river and monitor the quality of its water.

And as it turns out, it’s not as simple as you might think.

Melissa Pierce: There’s a lot of different ways that you can measure water quality and monitor water quality. You can’t tell just by looking at the water if it’s clean or dirty. We actually need to test it. And one of the ways historically that that has been done is by looking at the microbial population, specifically fecal coliform bacteria.

So fecal coliform bacteria are a group of bacteria that we call indicator organisms. They are found in humans and warm blooded animals. And we excrete them in our waste. So their presence can be indicative of other pathogens from human and animal waste in the river. So that’s something that we monitor for in our H2Now program, which we launched in 2021, and does real-time microbial water monitoring in the Chicago River.

And the reason we do that is to help the public have an understanding of if they decide they want to go boating on the river one day during the recreational season, what their risk level is.

Nate: Interesting. OK, so we’ll wait for that train to go by. And then I think we can continue.

After a quick break, we head over to current headquarters to escape the train noise.

And we’ll go way back in time to understand why we’re testing for human waste in the river. Then later in the show, we’ll head to Washington, DC to understand how another river is helping one scientist define an emerging field focused on the chemistry of our rivers. Stick around for more of the show.

The History of Chicago’s Waterways

All right, and we’re back with Melissa Pierce, the Technical Program Director at Current.

Melissa Pierce: Yeah, so it was a little noisy on the river. So we migrated to a little bit more of a quiet environment.

Nate: And we’re current-ly sitting in the conference room of Current HQ.

Melissa Pierce: Yeah, we call it the H2O suite sometimes.

Nate: Which is located just a few blocks away from the river.

Melissa Pierce: Location number two. Testing one, two, three.

Nate: And we’re going to go way, way back to imagine what life was like in the early days of Chicago.

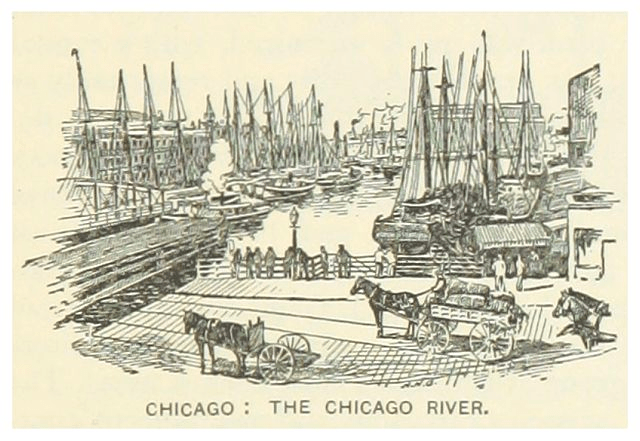

Melissa Pierce: So historically, Chicago has not had the greatest reputation for water quality of our waterways. And that’s because in the 1800s, Chicago was undergoing rapid industrialization.

Nate: The city’s population was growing. The economy was growing.

Melissa Pierce: And people were dumping human waste, industrial waste and industrial chemicals, animal carcasses from the slaughterhouses, trash, all kinds of things were just dumped into the river.

Nate: Dumping all that stuff into the river was not a good idea because the river flowed into Lake Michigan at this time. So all of those chemicals and carcasses were flowing from the river into the lake. And that’s what people were drinking.

Melissa Pierce: So all that pollution was negatively impacting the quality of the lives of people in Chicago.

And there were no laws at the time to protect the lake. So things were bleak for water quality back then.

Efforts to Improve Water Quality in Chicago

Nate: As you can imagine, the polluting of the drinking water was becoming a serious problem. Something needed to change if Chicago was going to continue to grow.

So folks got together and decided to reverse the flow of the Chicago River.

Melissa Pierce: So that, yeah, instead of flowing all of our trash and sewage into the lake, we would send it down ultimately into the Mississippi River. And so they undertook what was at the time the largest civil engineering project to dig the sanitary and shipping canal, which ultimately would help reverse the flow.

So that was completed in 1900. And so then our sewage was no longer going into our drinking water source, but ultimately down into the Mississippi.

Nate: This was a big deal. Reversing the flow of the river was a major engineering achievement. But it was an achievement that the city of St. Louis wasn’t too thrilled about.

They sued Chicago for sending all of the city’s waste down through their backyard. But ultimately, St. Louis lost, and they ended up having to build a filtration plant to deal with all of Chicago’s waste. Despite this victory and engineering marvel, Chicago still had some problems with its sewer system.

Melissa Pierce: So Chicago has what’s called a combined sewer system. So it includes residential waste, industrial waste from companies, and also rainfall, precipitation, stormwater, whatever you want to call it. So all of those things mixed together in our sewer systems. What happens is when we have a lot of rainfall and heavy storm events, the sewer system gets completely overwhelmed. And we get overflow into our rivers and our lake.

Nate: Sewage would back up in the basements or come out of sewer drains in the road. When this would happen, it’s called a CSO event.

Melissa Pierce: Which stands for Combined Sewer Overflow Events. And so in a CSO event, the sewer infrastructure is not able to keep up with the volume of water and sewage that’s being pushed into it. And it will literally overflow from the roadways into the lake or into the river.

Nate: And so these CSO events were having such a negative impact on the water quality that the government passed the US Clean Water Act in 1972.

Melissa Pierce: And because of the Clean Water Act, we now had to abide by federal and state regulations for water quality.

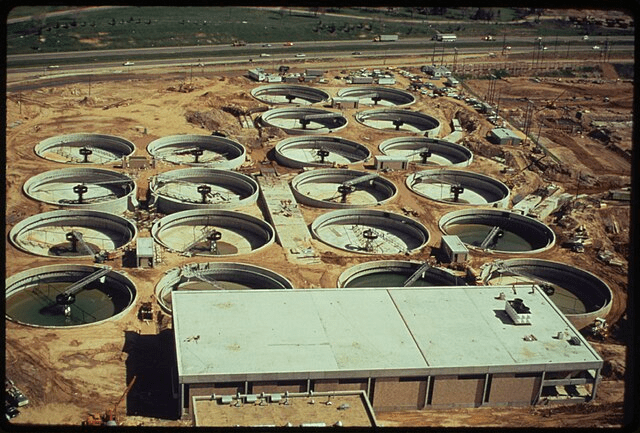

So the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, or MWRD, launched something called the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan, or TARP. This is one of my most favorite things to talk about. It’s so cool. So MWRD created this huge project. I think today it is still one of the largest civil engineering projects that’s ever been completed.

It’s a series of big tunnels that feed into reservoirs. And so when there’s a heavy rainfall event, that water gets diverted into those reservoirs so that when the water levels go down, that water can safely be pumped through water reclamation plants to be treated and cleaned. And that way, our sewer infrastructure isn’t overwhelmed, and we don’t have these CSO events where sewage is going into the lake and rivers.

So that was a really big deal. It was launched in 1981. But it’s still ongoing today. They’re still expanding the capacity of the reservoirs. So when it’s completed, it will hold 17.5 billion gallons.

Current State of Chicago’s Water Quality

Nate: So we’ve done all of this work to try to help stop these CSO events, which leads me to the really big question. How safe is the Chicago River?

Melissa Pierce: Yeah. So in 2012, the EPA essentially gave us a thumbs up for recreational activities on the Chicago River. So that’s one of the ways that you can know, is looking at regulatory decisions from organizations like the EPA. But also, you can check our website. We have gauges for each of the locations that we have one of our monitoring devices.

And it tells you, based on those estimated fecal coliform numbers, if the water quality is good or if you should exercise low caution or high caution when you’re engaging in recreational activities on the river. So you can check those gauges on our H2Now website.

We’ve put a link to the H2Now website in the description. So we’re going to go take a quick break. You go check out those gauges.

And when we come back, we’ll travel to DC and meet a scientist who is digging deeper into the topic of urban water chemistry, literally. We’re going to go all the way to the bottom of the river to understand how studying sediment can help us understand the chemistry of our waterways.

Stick around.

Exploring Urban Water Chemistry in Washington, DC

All right, we’re back.

Hello.

Steve MacAvoy: Hi, Nate.

Nate: This is our next guest, Steve MacAvoy. Steve is a professor at American University in Washington, DC. And ever since he was young, he had two ambitions.

Steve MacAvoy: I always knew I wanted to do environmental work. And I was one of those weird people who figured out they wanted to be a college professor when they were 16.

And so I’ve been doing this for 20 years.

Nate: So let’s start off big. How would you even study a river? I mean, what would that research look like?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, I do a lot of work that’s on sediments. And so I’m less interested in what’s going on in the water column and more interested in what’s going on at the water sediment interface.

I take what’s called a clamshell sampler on a string. And you lower this thing into the river, and the clamshell closes, and you get sediments that way. So when I’m looking at the rivers, I will go to maybe five or six different stations that I’ve consistently been going to for the last 10 years. And I’ll sample once a month.

So I had this continuous record of organic contaminants. And also, up until recently, I was looking at calcium and magnesium and that kind of stuff.

Nate: And so all these things that we’ve been talking about, this all really falls under the study of urban water chemistry. So can we talk a little bit about that? And also, what are you even learning from these samples?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, this is an emerging field.

So it’s long been known that there’s pollutants in the environment from industry, right? And that’s not news. We’ve known that for 100 years. However, what we’ve been recently becoming more aware of is that there are components of the urban infrastructure that impact the water chemistry running over the infrastructure.

So for example, in Washington, DC, we have acid rain. Most of the East Coast has acid rain. And the acidity in the rain is dissolving concrete, the surfaces of roads. It takes off car paint. It does a bunch of very subtle chemical processes that are changing the chemistry of the water. So they’re making it saltier.

We kind of discovered that by accident. I started out looking at the sources of nitrogen in sewage in DC’s water. And I was discovering nitrogen and all that stuff that I was looking for. But also, I saw that the amount of calcium and magnesium in the rivers was much too high, given the geology of the surrounding area.

So that was a puzzle. And I was wondering what on Earth is going on. And then I began to realize that what was actually happening is the acid rain was dissolving the concrete. And in the time it takes for the water to hit concrete surfaces and then run off into the rivers, a lot of calcium is released.

So the water is getting saltier. Now, whether this is good or bad, I don’t really know.

Nate: And so why is it important to, I guess, know what sort of chemicals are in your water? What sort of things are in these rivers and waterways inside cities? Why is that important to know?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, it’s important because humans have transformed the landscape to such a degree that we have literally changed the geology of our environment.

And it’s impacting the rivers by making them saltier. And that’s not natural, right? So we don’t know how nature is going to respond to that. Also, we can’t really fix it. It’s not an environmental problem like a pollutant that you can put a Brita filter on your tap water and it’ll take the contaminants out of the tap water.

We can’t do that in this case. It’s this insepant, universal feature of living in an urban environment. And it’s just an example of an unintended alteration of the environment. And we need to be aware of the consequences of our unintentional acts because frequently down the roadways, we’ll be like, oh, gosh, we shouldn’t have done that.

I can give you an example of something that’s happening right now in my laboratory. That’s a good illustration of this. We’re finding in the rivers and the sediments these compounds called siloxanes. And siloxanes are silica oxygen carbon compounds that nature does not make. When you see them in the machine, they’re clearly not natural.

They’re like a synthetic organic silica thing. And that’s a new chemical class that no one’s really aware of. But the Europeans have banned the smaller ones in cosmetic products. The Canadians are thinking about banning them. And the United States doesn’t pay any attention at all. But we’re finding these compounds in the stream water.

There’s no treatment process for it. You can’t remove them. And we know that they interfere with fish development. Okay, well, why does that matter? Well, fishes are vertebrates just like we are. And they share a lot of the same systems, hormone systems that we have. So we usually use fishes as a model organism to look for impacts of chemicals.

And so we’re seeing that. And we’re not paying attention. Like the government’s not paying attention. Industry’s paying attention a little bit because they know what the Europeans are up to. But anyway, it’s just interesting that we’re looking at these compounds and no one else is really paying any attention.

But that will definitely change.

Nate: Mm-hmm. So how do some of these chemicals then just, how do they get into these waterways? We’re finding them there. Do we know how they’re getting there? –

Steve MacAvoy: We have some good guesses. A working hypothesis I have is that for these siloxane chemicals, because they’re used in cosmetics, I think they’re probably in the sewer system.

And one of DC’s major problems that they’re trying to fix, but it’s still a major problem, is that when it rains, there’s frequently combined sewer overflow. So the sewer system and the stormwater system in the older parts of Washington, DC are combined, which is a terrible idea, but they built these systems in like the 1800s, early 1900s when there were a lot less people and they weren’t really worried about sewers overflowing into rivers.

It wasn’t a big deal to them. But I think because we do have this combined sewer stormwater system that the cosmetics are getting into the rivers. But siloxanes are very common compounds. And so any kind of like aquarium sealant, it’s a, well, it’s silicon. So you can go to the hardware store and buy it, right?

And normally we use it for sealing windows, but it’s also in haircare products, most lotions, wrinkle reducing creams, shampoo. And so they’re definitely in sewer water. And that’s probably the source, but we don’t really know.

Nate: And so once these chemicals like siloxane, once they do get into the water, do we know what sort of effects that can have on the streams?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, we’ve done laboratory studies using water from different locations in the Anacostia in DC, which is the main river that we study. And we found that it can kill embryos up to 14 days after fertilization. So in some cases it’s just killed them. And in some cases at lower concentrations, the fish don’t die, but their behavior changes and the behavior is a stress behavior.

So there is an impact on their physiology and it stresses them out. Now, the thing with the Anacostia is that in general, things are getting better. We’ve been working on trying to clean this river for almost 15 years and it’s getting better, but this is just another compound that is added to the things to be aware of and kind of be concerned with.

But at the same time that we’ve been monitoring siloxanes, we’ve also watched the PAH concentrations. PAHs are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that are known carcinogens and their concentrations are going down. So that’s really good. And actually about 20 years ago, there was a study that was looking at catfish in the Anacostia and they found that 80% of the female catfish had cancer.

Then they did a follow-up study about 10 years ago and they found that only 40% of the females had cancer.

Nate: I mean, that’s better.

Steve MacAvoy: But it’s still horrifying, but it’s an improvement. And then a couple of years ago, they went looking for catfish again and they didn’t have any cancers at all. And it’s likely that the cancers were caused by PAHs and the concentrations of those have been going down.

And so that’s a good story. And so I think the river is on its way to recovery, but it has siloxanes in it. But the siloxanes probably aren’t giving fish cancer, but they might harm embryos.

Nate: Right.

Steve MacAvoy: But there’s a lot of things in rivers that harm embryos. So it’s just another environmental stressor.

Nate: And so this is a new field. So what are some of the concerns that we’re having as we’re starting to figure out more and more information about how chemicals in river water can affect both the natural ecosystems that are already there and us?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, this is a interesting question. I think it’s a good idea for people to be aware of what’s in their water.

So if you can get that information from the government, which presumably is doing water testing, people should check that because there’s some compounds that are in our water that are not taken out by sewage treatment plants. In Washington, DC’s case, all of our water comes from the Potomac River. The Potomac River itself is highly recycled.

Basically it’s wastewater that has been treated and released. And so there’s compounds in the water that are complex organics like pharmaceuticals. So there’s pharmaceuticals in the water. Antidepressants, for example. Some cancer medications are in the water. So I would say it’s a good idea to have a water filter, even if they’re treating the water with chlorine or bromine or something that’s gonna kill the bacteria, there might be compounds in the water that you don’t necessarily wanna drink.

So I would recommend that if people in cities are drinking recycled water, it’s probably a good idea to get a filter.

Nate: And in cities where water is recycled from rivers, how would that happen? And what are some of the ways that these chemicals can still get through?

Steve MacAvoy: Yeah, so the Potomac River has a lot of people who live along it and it’s a fairly large watershed. So there’s a lot of communities that are treating and then releasing their wastewater through a sewer treatment plant.

So when I say the water’s recycled, that’s what I mean. It’s been through someone’s water treatment plant. And then of course it goes through DC residents and then we release it from our sewage treatment plant that’s south of the city. Now, the thing with the treatment plants is they take care of bacterial contamination and they monitor that to make sure it doesn’t have bacteria in it.

So that’s good. They take care of the suspended solids, right? So the settling tanks and all that. They don’t take care of nutrients, it’s like nitrogen or phosphorous. Those aren’t normally taken care of. And then also organic chemicals that are in the sewer water. That’s not cleaned. If it’s dissolved in the water, it just stays in the water.

Now, there are some treatment plants that have what’s called tertiary treatment. And what happens there is the water, after the bacteria have been killed and after the solids have settled out, they’ll actually put the water through a marsh or some kind of artificial wetland. And the wetlands will take care of the organics and the nutrients.

That’s called tertiary treatment and it’s expensive. And it also increases the size of the footprint of the treatment facility. And so it can’t be done everywhere. But we need more of that to really clean the water and make it a little safer.

Nate: And so, like you’ve said, this field is just starting to form. And so going forward, what sorts of things should we be watching out for, I guess, as we’re continuing to monitor what we’re putting into our rivers?

Steve MacAvoy: Well, one really important thing is to keep monitoring the rivers because we have environmental policies that are aimed at trying to clean up the systems.

Now, in order to know if your policy is effective, you have to go and look at what happens after the policy is enacted. And then to figure out if like, well, did we miss anything? Is it too stringent or is it not stringent enough? And so we need monitoring to assess that. So in a response to acid rain, there’s been a set of clean air acts, right?

Two of them that have tried to clean the sulfur out of the air or prevent it being released, I guess is a better way to say it. And so we’re tackling the acid rain problem, but we have to monitor the river’s response to know if it’s effective. And I’m happy to say it is effective. So actually among the myriad environmental problems that we have, the acid rain problem is actually getting better.

So there are some good news stories, but it takes 20 years to see the effect. So, you know, it’s slow, oh my gosh. I mean, also, okay, I’ve been in DC 20 years. So I’ve been here long enough to see changes to the good side, right? I’ve watched effective policies. And so it is possible to do this, but you do have to monitor it.

Nate: Yeah.

The Future of Urban Water Management

So given that it takes so much time to see these results, it’s important for our future to have effective policies in place right now.

Melissa Pierce: Yeah, so if you don’t mind me tangenting for a couple more minutes, you know, water is this critical resource and in cities of the future, water will only become more and more important.

Nate: This is Melissa Pierce again.

Melissa Pierce: We talk about the Midwest. The Great Lakes have 20% of the world’s freshwater. And so the Midwest has been designated as a place we’re gonna see a lot of climate migration, where a lot of people that are feeling intense impacts of climate change are going to be migrating to the Midwest, in part because of the Great Lakes and the freshwater here.

So it’s really important that we take care of it and that we’re really thinking about what we call water risk. And so when I say water risk, what I mean is like the challenges and the potential problems related to the availability of water, the quality of water and the accessibility of water. So is there too much?

Is there too little? Is it too dirty? Those sorts of things. So those are really important and also things that current is involved in and really trying to bring to the forefront of the conversation.

Nate: There you have it folks. The Show About Science is complete. Thank you so much to Steven McAvoy and Melissa Pierce for taking the time to chat with me. If you’re interested in learning more about water monitoring and the work current is doing in the Midwest, we have additional resources down in the description.

Definitely make sure to check out the River Lab program. This to continue this episode comes from Epidemic Sound and our theme song was written by Jeff, Dan and Theresa Brooks. Ad free episodes of The Show About Science are available on our website. And of course, make sure to subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to podcasts.

Okay, dad, you can shut the recording off.

Leave a comment