In this episode of The Show About Science, Nate unearths the surprising history of the Kentucky Coffee Trees growing in his backyard and quickly becomes obsessed with germinating their seeds. This obsession leads him to a lab at the University of Illinois at Chicago where he meets up with plant ecologist, David Zaya, to uncover the evolutionary tale of these trees and the role humans now play in preserving them.

Connect with The Show About Science:

Instagram: @showaboutscience

Facebook: @theshowaboutscience

YouTube:The Show About Science

Twitter: @natepodcasts

LinkedIn: The Show About Science

Threads: showaboutscience

Transcript

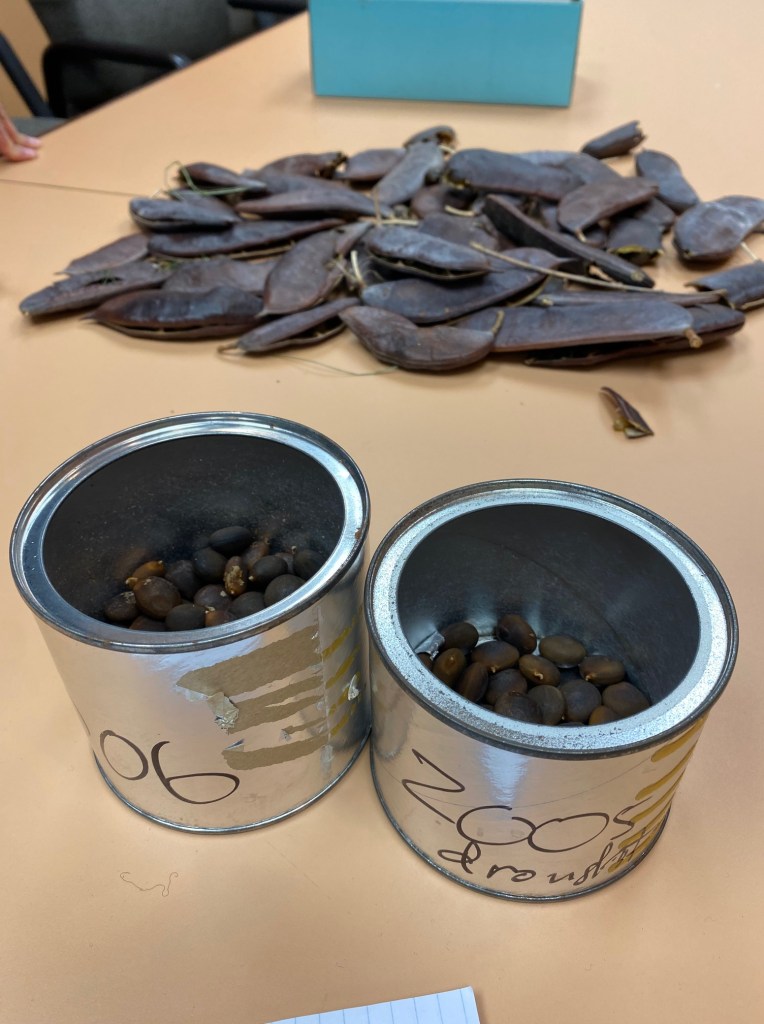

Nate: Hello everyone, Nate here, back with The Show About Science. And today, we begin with these two trees in my backyard. They’re both the same species, and every winter, they’re completely barren. But then as soon as spring comes in, they burst with life. They grow new leaves, they flower, and then they start to grow these really long, kinda gnarly, bluish-black seed pods. They look a lot like a flattened, overly ripe banana, but they’re crunchy, not soft. The seeds inside these pods, they’re about the size of a grape, and they have the thickest shells you’ll ever find. And I’ve always been obsessed with them. As long as I can remember, I would always go outside and find these seed pods and smash them. But one day, about a year ago, I decided, “You know what? I think I wanna grow these seeds.” I started researching. Pretty quickly, I learned that they were Kentucky Coffee Trees. And I didn’t know it at the time, but now I know the Kentucky Coffee Tree is a very unusual kind of tree. I turned to YouTube in order to get more information on how to grow these seeds, and I stumbled across a channel called Urban Roots. Well, technically it’s Herb and Roots. It’s a play on words, ’cause the host’s name is Herb. But anyways, they have a really good video on how to grow these seeds. And Herb, he kinda looks like he should be in a metal band, long hair, beard, all that. And in the video, he’s surrounded by all of these baby saplings. And the first thing he says is,

Herb: “What’s going on, folks? Today, we’re talking about growing Kentucky Coffee Tree from seed.”

Nate: And as soon as he said that, I was hooked. But actually growing these seeds is harder than one would think. Like, you can’t just plant them in the soil. That’s because of something called scarification. So remember how I said that these seeds have a really thick shell? That’s actually kind of a problem, because they need nutrients, and that shell is blocking those nutrients from getting through to the seed inside. In order to grow them, nowadays you have to cut a hole through the seed in order for them to grow. And in the video, you can tell that Herb’s a strong guy, and even he is struggling to scarify these seeds. And he’s talking about all of the different things that he’s trying to do, and none of it is working.

Herb: I started out with a woodworking file. That almost did practically nothing to the extremely hard seed coat. And I then moved on to a dovetail saw, and that did a little bit better, but it was still actually very hard. Harder than what you would expect with a hardwood like maple or oak. Well, I did use the file.

Nate: In the end, he used a file, a hacksaw, and boiled them in water. Just in order to get that little nick that he needed to get those seeds to grow. And this is one of the things that I found out, that they have a really hard time germinating on their own in the wild. And so they need human intervention to do it. And that kind of gave me like a whole new purpose in growing these. So I went to my dad for help, and he brought out a belt sander to sand down the shells of these seeds.

Bring out the belt sander.

We sanded them down so that there was a little hole in the shell. And then we also did the second method, which is to put them in a pot of boiling water. So we did all of that. We took them out after a day, and then we planted them in the soil. And after weeks and weeks of care, what we got was a pot full of dirt. Something had definitely gone wrong. So we tried again because I was determined to grow one of these saplings. So I got a new batch of seeds. So let’s open up the seed pot. This time I only sanded them down. I didn’t boil them in water. I put them in the soil and hoped for the best. Once again, after weeks and weeks, finally this time we actually got little saplings poking up through the dirt. I was overjoyed, but part of me was kind of wondering, why is this such a process? Why have these seeds evolved to have this thick shell that means that they can’t germinate on their own? That makes no sense. So I went back to the internet and I did some more research, and I have one answer for you. Prehistoric giants known as megafauna. And that answer has brought me here. Should we just…

David Zaya: Head into the building, yeah. Let’s go inside.

Nate: To the lab of David Zaya at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

David Zaya: Yeah, I’m David Zaya. I’m an ecologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, which is part of the University of Illinois. And I’m interested in botany and plants and how they interact with their environment.

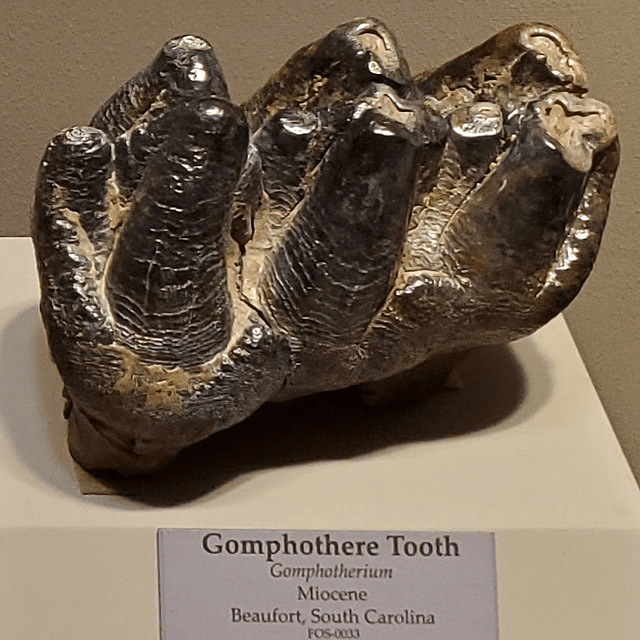

Nate: So how would you define megafauna? How would you define it?

David Zaya: Megafauna are really large animals. In this case, we’re talking about mammals. And when we think of gigantic mammals now, giraffes and rhinos and elephants, we think mostly of Africa. But between five and 20 million years ago, and even going further than that, North America had a probably larger array of really large mammals that went around eating stuff. So gigantic camels, ground sloths, horses, gomphidheres, which are related to elephants, and titanidheres, which look like rhinos, and mastodons, and a whole bunch of things. There were a lot of them, and they were big, and they were very influential in the landscape.

Nate: Just take us on this journey. So you see this big gompathier. What does it look like? And if it sees something like, I can tell you, coffee tree in the distance, what’s gonna happen?

David Zaya: So a big, bad gomphothere probably will just eat whatever it can reach that isn’t too sharp or too poisonous. So it sees a Kentucky Coffee Tree in the distance, and it’s like, oh, I’ll eat a whole bunch of stuff on the way there. And it’s just this indestructible, well, almost indestructible chomping machine.

And then it finally gets to the Kentucky Coffee Tree, and it’s like, oh, let’s say it’s November, the fruits are nice and ripe and tasty and sweet, and just picks off hundreds of them off of a single tree, and then it’ll go to another tree and pick off 100. Eat them, some of them will be chewed and nicked and fall out of its mouth. So that’s a lot like you sandpapering them down and germinating, and some will get swallowed along with the fruit and go through the stomach, become exposed to acid and be pooped out in piles. Then also another thing about Kentucky Coffee Trees, it’s very resistant to pathogens. So although it’s sitting in a big pile of poop, it has the ability to fight off diseases and the rot that might come to it. –

Nate: And that poop is also probably pretty nutrient rich.

David Zaya: Yes, that’s right.

Nate: Yeah.

David Zaya: And then it germinates and grows up into seedling and potentially eventually a tree.

Nate: But so this was 5 million to 20 million years ago, right?

David Zaya: Yeah.

Nate: Yeah.

David Zaya: Something like that, yes.

Nate: But I don’t see any elephant sized creatures walking around Chicago. I haven’t heard of a gomphothere in my backyard before. So what happened?

David Zaya: There were a few things that happened. So the peak of the gigantic wild mammals of North America was something like 20 million years ago. And a lot of them went extinct due to probably changes in climate and seasonality and things like that. But even 100,000 years ago, up to even 15,000 years ago, there were large mammals. Mammoths are the ones we think of the most, but not just mammoths, around North America. And mammoths wouldn’t eat these probably, but other things, they were probably chomping on them. Now what happened 10 to 15,000 years ago is a huge controversy. There’s this hypothesis called the overkill hypothesis, which is that humans moved into North America about the same time that mammoths disappeared. And is it that they hunted them so quickly that they went extinct? Or is it that the weather changed, which caused mammoths to disappear and also allowed humans to come in almost immediately afterwards? It’s an interesting debate. I have an opinion on it, but I don’t know if I want to.

Nate: But what’s your opinion?

David Zaya: My opinion is that until we find a large number of mammoth bones associated with human…

Nate: Like with spearheads in them or something?

David Zaya: Or in piles near where people lived, that we have to assume that it’s just correlated, meaning they happen at about the same time, possibly for the same reasons, but one

Nate: But they weren’t related to each other.

David Zaya: One didn’t cause the other.

Nate: Yeah.

David Zaya: Yep.

Nate: Okay, so what did the loss of these massive mammals that used to eat and disperse their seeds, what did that do to trees, like the Kentucky Coffee Tree that relied on these mammals in order to make new trees?

David Zaya: For individual plants, for individual species, like Kentucky Coffee Tree, it’s probably a lot rarer today than it used to be, and it probably occurs in fewer types of places. So a lot of times this plant is found along rivers or kind of close to a flood plain because the fruit happens to float or near old human habitation, so Native American habitations, because they use the seeds as games and toys and also for a kind of a drink that was kind of like coffee, that’s where the name comes from. So it became rare and then where it grows became less. For the larger plant community, it probably changed a lot. It probably became a lot more homogenous, the same. Now North America has a very small fraction of the habitats that it used to, probably because of the smaller fraction of types of mammals on the landscape.

Nate: Okay, so just having like the mammals that they used to rely on go extinct, that caused a significant drop in the number of Kentucky Coffee Trees and other trees like it that rely on these mammals. So because of that, they were really only found in places where they could luckily still grow. But so from there, this hard shell on their seeds that used to be an asset, that used to allow them to be propagated by these massive megafauna, that has now kind of become a detriment, right?

David Zaya: Yeah, so that’s called an anachronism, meaning it’s adapted to something that doesn’t exist anymore, to something in the past. The thing about Kentucky Coffee Trees is they really stick out as extreme examples. So I don’t mean to get too theoretical, but in a sense, everything is an anachronism to its past. Everything has traits that are due to evolutionary forces from a million years ago. It’s just that Kentucky Coffee Trees have this cutoff point 15,000 years ago where big things disappeared.

Nate: Like it’s very, very clear.

David Zaya: It’s very extreme, yeah. So the honey locust tree has, for example, these 10-inch long spikes that grow all up and down the trunk that are extremely sharp. And it’s like, why? It’s like, oh, so if a giant sloth came by, it didn’t lean too hard against the trunk and tear the whole thing down when it was picking off the pods. It would just gently lean on it kind of thing.

Nate: So basically, an anachronism, if I’m getting this right, it’s when a trait that used to be like an asset to a species, like specifically for the Kentucky Coffee Tree, this hard shell that used to allow them to be eaten by these massive North American mammals that are kind of similar to rhinos, that used to allow them to be eaten by those creatures. And then it wouldn’t be destroyed by their stomach acid and it would be pooped out along with their poop. But after they went extinct, this trait is just floating there in limbo. Like it doesn’t have a use, but it’s gonna take a while for it to de-evolve that trait. So it’s just there and it’s actually starting to make life harder for the tree.

David Zaya: Yeah, it is making things harder. It’s making the tree less common in fewer places, but life is still going on.

Nate: Life finds a way.

David Zaya: It finds a way, yeah. So it’s kind of a useless trait, but after 13,000 years with nothing big enough to eat it, it’s still there.

Nate: So are there like any other examples of evolutionary anachronisms like in us or in other mammals, or is it like an exclusively plant or tree thing?

David Zaya: There are. If you start looking, you’ll find anachronisms all over. So a great example is how poisonous things are in Australia, like spiders and snakes and all types of creatures, extremely venomous, extremely poisonous. And the question is why? Why are there like five of the top 10 most venomous snakes in Australia where there’s nothing really to threaten them before humans brought larger animals? It’s probably because Australia had a bunch of large animals, mammals also that maybe were predators or competitors and the such. So that’s an example in animals. In humans, a lot of times we talk about vestigial traits, like our tailbone, where we used to have a tail, but no longer have a tail.

Nate: And so that’s kind of related because it’s also something that’s still there. That’s like a remnant of something that once was, but it’s not exactly the same ’cause this is like another species going extinct, which leaves behind this useless trait in another species versus like something that’s just kind of a relic of our past.

David Zaya: Yeah, that’s right.

Nate: Yeah. The megafauna went extinct thousands of years ago, but the Kentucky Coffee Trees are still here. And that’s probably because of humans. But the question is, could they still have survived even without us?

David Zaya: Yes, I think they would have survived in fewer places and in fewer types of places. So a lot of times you’ll see them on hilltops. I don’t think they’d be there anymore. They would stick to kind of the edges of river floodplains. There is a species where I could point out that I don’t think would exist without human intervention. And that’s the ginkgo tree, which has this really foul fruit that isn’t really a fruit, but it’s so ancient. It evolved before flowers and dinosaurs were probably eating and spreading the seed. And it was thought extinct, except they found it in China associated with religious temples.

Nate: So without like those religious centers in China that were like keeping them there because they kind of looked pretty, you don’t think that those trees would have survived?

David Zaya: That’s my guess. I don’t think there would be any more ginkgo trees.

Nate: But we have definitely brought them back from like that somewhat brink, I guess.

David Zaya: Yeah.

Nate: ‘Cause I have a couple of ginkgos on my street. I’m sure that some listeners probably have also like seen them or have them growing near where they are.

David Zaya: And they’re gorgeous.

Nate: Their leaves are so unique, definitely. So I can understand why we’ve kept them around.

David Zaya: Yeah.

Nate: The thing I really got from talking with David was that he’s just as passionate about Kentucky Coffee Trees as I am. And really that all began when he was young.

David Zaya: So yeah, I became very obsessed with Kentucky Coffee Trees. I would give the seeds as gifts. I would keep them in my pocket and then get really polished and give them away. And my friends actually asked me to stop talking about them so much at one point. And why? First, I think they’re really cool looking. You have that branch that is, Gymnocladus is its scientific name, which means naked branch. It’s bare most of the year. Six months out of the year, there’s nothing on them. And then they have those gigantic fruits with this sharp point and these seeds that are just perfectly like marble shaped toys. And the leaves, if you look at a leaf, it’s actually made of a bunch of leaflets and each leaf is made out of a hundred or so, not each leaf, but many of them, most of them are made out of a hundred leaflets. So you can take down a leaf and just looking at it is like, I don’t know, it’s a beautiful pattern that has just captured my imagination. I don’t know how to explain it. [laughing]

Nate: It was kind of crazy just how closely David’s story mirrored my own. But there’s still one more piece left in my story that we haven’t talked about yet. So after learning all this stuff about how important humans are to this tree species survival, I kind of went on a tree growing rampage. [upbeat music] So I think I grew like 12 more trees. It was so many that I was growing them in red solo cups ’cause I had long since ran out of pots. And by this point, some of the bigger trees were beginning to grow out of their red solo cups. So I had just gotten this bicycle that I would use to ride around on and visit all these different garage sales where I’d buy a pot, then bring it back home and replant the Kentucky Coffee Tree into that pot and then use the red solo cup that it left to grow another Kentucky Coffee Tree. So I was just growing more and more and more and more and more. And by this point, it was nearing the summer. And so at the end of the school year, I was giving all the ones that I still had out as gifts to my teachers. And one of these gifts went to my reading teacher, Ms. Linehan, who is awesome by the way.

Ms. Linehan: And I asked Nate to tell me a little bit about it. And he said it was a Kentucky Coffee Tree plant, that it would grow incredibly tall, that it would be an incredibly tall tree one day and not to actually brew the coffee beans that they were toxic and so to be careful of that.

Nate: Obviously, this is Ms. Linehan. And she took home her little Kentucky Coffee Tree sapling to her apartment and just had it growing on the balcony for a couple of weeks.

Ms. Linehan: There were days where you could almost measure the growth by the day, it just was really thriving.

Nate: Then one day her parents came for a visit.

Ms. Linehan: And my dad was especially taken with the Kentucky Coffee Tree plant.

Nate: And they were talking about how big the Kentucky Coffee Tree is gonna end up getting. And in the end, they decided that it couldn’t just live on her balcony forever. So they decided that Ms. Linehan should drive up to Wisconsin where her dad could plant the tree in their yard.

Jack Linehan: When I got the tree, it was a little fragile, a little sapling, but it looked pretty healthy, very healthy. I was in that red solo cup.

Nate: This is Jack.

Jack Linehan: I’m Ms. Linehan’s dad.

Nate: Jack repotted the sapling and brought it inside for winter. Although in the end, the tree didn’t make it. But it didn’t matter because now Jack was obsessed with these trees too.

Jack Linehan: I really wanted to keep the potential of having our own Kentucky Coffee Tree. So I placed an order online.

Nate: A few days later, new Kentucky Coffee Tree saplings arrived on Jack’s doorstep.

Jack Linehan: I planted them, it’s been about two weeks now. And two of them are showing new and unfolding leaves already and looking quite healthy, looking quite normal for this time of the year.

Nate: And so in the end, both human intervention along with a healthy dose of obsession with this tree species has led to us kind of acting like how the megafauna used to. And that we’ve been able to spread the seed far from where its parents were. And I find that kind of poetic, I guess, that thousands of years later, humans are kind of playing the role for these trees that giant sloths and other megafauna used to thousands of years ago.

Bring out the belt sander. And the idea of this repeating generation after generation. Yeah, I find that kind of awesome to think about.

Bring out the belt sander.

There you have it folks, The Show About Science is complete. Special thank you to David Zaya and the Linehan’s. And music on today’s episode comes from Blue Dot Sessions. As always, our theme music comes from Jeff, Dan, and Theresa Brooks. Additional production and editing comes from Tim Howard in Berlin. You can shut the recording off.

Leave a comment